. I have been here before. I have never been here before. I have been here before. I have walked up the path to the Zen Temple. The temple lies just where I remember it, just as it should; no, just where it has to; no, it just lies. When the archer looses the arrow, it is already in the target.

. I have been here before. I have never been here before. I have been here before. I have walked up the path to the Zen Temple. The temple lies just where I remember it, just as it should; no, just where it has to; no, it just lies. When the archer looses the arrow, it is already in the target.It’s raining lightly, a taifun curling its wet, scaly tail round the Inland Sea. I pause at the corner of the verandah and look out onto the rounded hips of the slope be

hind. Rain drips lightly off the eaves into the moss. I know why I’ve come.

hind. Rain drips lightly off the eaves into the moss. I know why I’ve come.10,000 miles is not too farBasho didn’t like Zuiganji much. He was craving for something simpler: “…the temple was enlarged under Ungo Zenji into seven main structures with new blue-tiled roofs, walls of gold, a jewelled Buddha-land. But my mind wandered, wondering if the priest Kembutsu’s tiny temple might be found.”

to hear rain dripping into moss

at Zuiganji

Now, more than 300 years later, Zuiganji has mellowed and settled into the landscape. Less of ‘what should be’ and more of ‘what is’. Round the back ‘36 retainers committed seppuku when their lord died’. A lifesize china doll replica of the said Lord, Date Masamune, scowls in the museum, his helmet crested by the keen sickle of the ascendent moon. Trainee Zen monks sculpt the bushes next door into ‘natural’ shapes, stepping back to inspect their handiwork.

‘Natural’? Don’t tell me a Zen Garden is ‘natural’!

It’s as precision manufactured as Mitsubishi steel.

If you want ‘natural’, see under ‘m’ for ‘malaria’!

I wander off up a track and a monk comes after me to tell me I’m intruding. I start to mention Dogen Sangha in England, but desist. I’m in Japan, in a traditional Zen temple, and here you probably have to sit in the Lotus position for 50 years before you’re even qualified to kiss the Master’s arse.

Kissing arse fineThe local train stops at Nobiru and I trudge under fir trees th

but what is Zen actually about?

HERE! HERE!

rough a shower and the gathering dusk to Oku Matsushima Youth Hostel, where I have a six-bunk room to myself. Jets on training flights from the nearby airfield fly past in perfect unison miles above my head.

rough a shower and the gathering dusk to Oku Matsushima Youth Hostel, where I have a six-bunk room to myself. Jets on training flights from the nearby airfield fly past in perfect unison miles above my head.That night, and the following, I dream consecutive dreams of women. I go to sleep, dream of my wife, wake up, write poetry f

or 2 hours, go back to sleep, take up the dream where it left off, dream of a past girlfriend.

or 2 hours, go back to sleep, take up the dream where it left off, dream of a past girlfriend.The shadow of my bunk measures the slow hours of night;

the voice of the sea-goddess beckons from the waves: come drown in my body!

This goes on for two nights. Why? The

n I remember. Basho, landing at Ojima Beach, Matsushima, writes: ‘…alighting at Ojima Beach, one is almost overcome by the sense of intense feminine beauty in a shining world’.

n I remember. Basho, landing at Ojima Beach, Matsushima, writes: ‘…alighting at Ojima Beach, one is almost overcome by the sense of intense feminine beauty in a shining world’.Island dotted after island: piggy-backed, mother-baby, father, grandfather. Careless goddess-strewn islands fertilized by sea-god sperm. Red pines ache to connect heaven and earth. The ancients have left messages. Oh Matsushima!

I take a final wander along the beach.

In the sands of Nobiru Beach

I write the name

of every woman I have ever loved

Then I take the train back to Sendai.

[click here for satellite imagery of Matsushima]

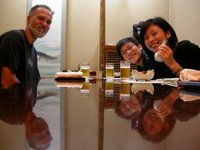

Heading North, I change for Ikinoseki, then catch a bus to Hiraizumi and a local bus to the ryokan ‘Okkiri-so’. The owner is waiting for me outside and bustles me in, gabbling away all the time in Japanese. I have a quick soak in the communal bath to shake off the dust of the journey and join the other guests in the dining-room. Hilarity reigns from the onset. Not only does this stupid gaijin not know how to sit, um, decently in his yukata (at a table 6 inches above the ground), he also obviously doesn’t know what to do with the assorted cooking paraphernalia and medl

ey of little dishes on his table.

ey of little dishes on his table.Like a fish out of water, I gape at a flood of Japanese;The other guests – all men – seem to be either utility servicemen or travelling salesmen. One offers me sake onzarokku. Yes

hauled over to translate, guy at next table says, "broiled salmon testes!"

I flip over and die

– sake on-the-rocks. The giggling owner – but she’s giggling with me, not at me – shows me how to light the brazier and cook my own food, to my own liking. The thin-cut beef is delicious, the miso soup - but some of the other ingredients…well, thebrain is willing, but the stomach is another matter.

– sake on-the-rocks. The giggling owner – but she’s giggling with me, not at me – shows me how to light the brazier and cook my own food, to my own liking. The thin-cut beef is delicious, the miso soup - but some of the other ingredients…well, thebrain is willing, but the stomach is another matter.You don’t walk on your feet, you walk on your stomach! Food so fresh it’s still wriggling. Kill it! Burn it! Eat it! Great Hairy Northern Barbarian prefer well dead and well cooked! Sink teeth into Japanese schoolgirl butt! Nyugg!

Then I have a MacBreakfast.

Then I have a MacBreakfast.