Wanna go to Naruko-onsen.Nearly all gaijin tourists have a Japan Railpass. You pay a fixed amount and can travel anywhere you want for 1,2,3 weeks, depending. Sounds like a good deal, but I wasn’t so sure. It encourages ‘railpass tourism’, ‘ticking the boxes’, ‘getting all the sights in’. I thought that were I to find somewhere nice and wanted to stay for a while I’d feel I couldn’t – I’d be wasting my precious Railpass. So I didn’t get one.

"Shikansen?" asks unhelpful tourist woman.

"Iie (no)”, I say

"Ah," she says, "change Kogota!"

The trains I take – apart from being cheaper - clack along slowly, stopping often to pick up and disgorge schoolkids, peasant women bent double after a lifetime of rice farming, people with interesting faces. I can see into backyards, admire the topiary in front gardens. You don’t get that at 300kph in a shikansen (bullet train).

No need to get anywhere,I ar

no hurry.

Sun at Hiraizumi Station

rive at Naruko-onsen, drop into the Tourist office, drop into Takishima Ryokan (Has rather a ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoos Nest’ feel but does the job, says The Lonely Planet guide – they’re right, the place has rather an air, as does the wistful owner), then dash up the road to Taki-no-yu, an ancient and venerable onsen (hot-spring). Taki-no-yu is the holy bath of the nearby Shinto Shrine and has more than 1000 years of history. It has ‘hardly changed over the last 150 years’.

rive at Naruko-onsen, drop into the Tourist office, drop into Takishima Ryokan (Has rather a ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoos Nest’ feel but does the job, says The Lonely Planet guide – they’re right, the place has rather an air, as does the wistful owner), then dash up the road to Taki-no-yu, an ancient and venerable onsen (hot-spring). Taki-no-yu is the holy bath of the nearby Shinto Shrine and has more than 1000 years of history. It has ‘hardly changed over the last 150 years’.I pay my 150 yen (75p – who said Japan was expensive?), dis

card my clothes, scrub up and literally drop into the main male bath. ‘Scrub up?’ – yes, in Japan one washes before getting into the (communal) bath. The bath is steaming hot and meant purely for relaxation and soaking, not washing. Getting ready to bathe is a whole ritual in itself, sitting on a little wooden stool, pouring water over oneself, soaping, more water, ears, hair, back of neck, cracks between the toes, gargle, spit …

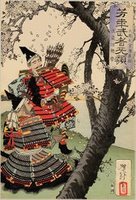

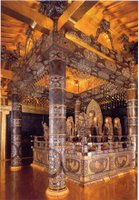

card my clothes, scrub up and literally drop into the main male bath. ‘Scrub up?’ – yes, in Japan one washes before getting into the (communal) bath. The bath is steaming hot and meant purely for relaxation and soaking, not washing. Getting ready to bathe is a whole ritual in itself, sitting on a little wooden stool, pouring water over oneself, soaping, more water, ears, hair, back of neck, cracks between the toes, gargle, spit …At Taki-no-yu everything is cedar – the main walls, the partition dividing the male and female baths, the bath itself, and even the pipes bringing the stinging hot, milky water in. A youngish guy with a blood-curdling tatoo of a samurai severing someone’s neck covering the whole of his back barges through the swinging door, scrubs up and drops into the bath. A yakuza (Japanese gangster). I’m sitting in a bath with a naked yakuza! He doesn’t, fortunately, seem too interested in severing my neck just at the moment, perhaps because we’re in a holy bath. Anyway, I can’t seem to worry about it too much. The water’s blissing me out. I soak for as long as I ca

n take the heat, then get out.

n take the heat, then get out.a bunch of marigoldsAs I leave Taki-no-yu, bending low to brush aside the door hanging, dusk is descending. Outside, red lanterns sway gently in a slight breeze, beckoning guests in t

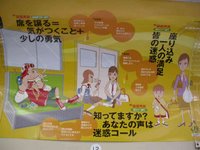

in the toilets

at Taki-no-yu

o low-beamed, traditional-looking places to eat. A sudden clack of geta (traditional wooden clogs) and an underlay of voices as a mixed group of visitors, male and female both clad in the same blue and white yukata, rustle past. A scene which could have come down unchanged through the centuries, the millennia. In a daze, feet scarcely touching the ground, I wander off to find something I can eat.

o low-beamed, traditional-looking places to eat. A sudden clack of geta (traditional wooden clogs) and an underlay of voices as a mixed group of visitors, male and female both clad in the same blue and white yukata, rustle past. A scene which could have come down unchanged through the centuries, the millennia. In a daze, feet scarcely touching the ground, I wander off to find something I can eat.The next day I go in search of Basho.

Beyond Narugo Hot Springs, we crossed Shitomae Barrier and entered Dewa Province. Almost no-one comes this way, and th

e barrier guards were suspicious, slow and thorough. Delayed, we climbed a steep mountain in falling dark and took refuge in a guard shack. A heavy storm pounded the shack with wind and rain for three miserable days.

e barrier guards were suspicious, slow and thorough. Delayed, we climbed a steep mountain in falling dark and took refuge in a guard shack. A heavy storm pounded the shack with wind and rain for three miserable days.Eaten alive by lice and fleas

now the horse

beside my pillow pees

All the main roads in Japan have massive dumper trucks thundering along them, transporting brother mountain to fill sister valley, steel girders to shore up the consequent gaps, concrete to pin down her underskirts, stop her wiggling. Yet still she wiggles. Her hot flushes in summer bake everyone alive, her co

ld tears fall silently in winter from ashen cheeks, the snow drifting up to 5 metres high. In spring her waters break, rain falls endlessly, birthing new life, cicadas sing, the rivers burst their banks, get their fingers into the land and pull it apart. Then: EARTHQUAKE! She shrugs it all off. Dumper trucks scuttle along her veins and the humans put it all together again.

ld tears fall silently in winter from ashen cheeks, the snow drifting up to 5 metres high. In spring her waters break, rain falls endlessly, birthing new life, cicadas sing, the rivers burst their banks, get their fingers into the land and pull it apart. Then: EARTHQUAKE! She shrugs it all off. Dumper trucks scuttle along her veins and the humans put it all together again.I wander along the main road THUNDER, past the kokeshi factory THUNDER making brightly painted wooden dolls, pause to video young bloke making one THUNDER, up to modern bridge, cross the road THUNDER and down to shitomae-no-seki.

A reconstruction of the torii (gateway) stands here, alongside the old country track, a statue of the great man and an explanato

ry panel showing the barrier as it was then.

ry panel showing the barrier as it was then.Basho was treated suspiciously here;I put my notebook in the statue’s hands and a dragonfly alights on it, then takes off again. Dragonflys in Japan carry messages to and from the Land of the Dead.

there is a theory that he was a spy for

the Shogunate.

Freely passing Shitomae-no-seki, mist lifts off the valley